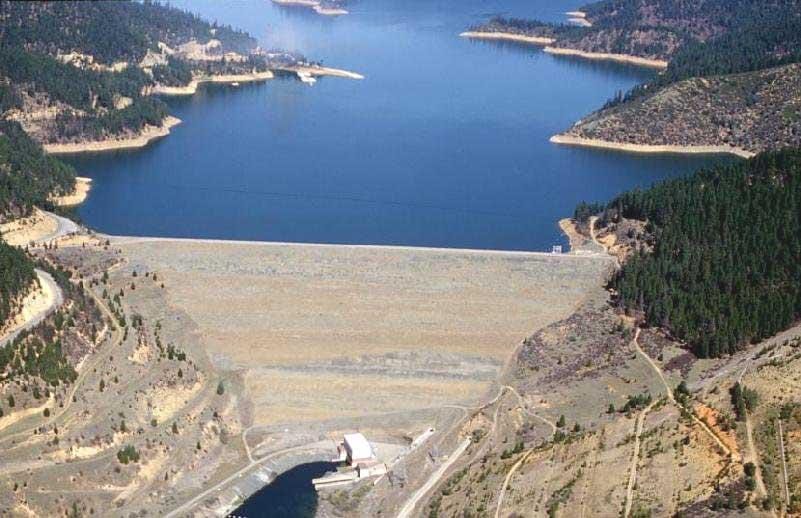

A 250 Ft. Wall of Water on the Trinity River Is Still a Big Threat

“If Oroville had overtopped, the surging water would’ve rapidly eroded the dam, ultimately unleashing a massive flood down the Feather and Sacramento Rivers.”

“If Oroville had overtopped, the surging water would’ve rapidly eroded the dam, ultimately unleashing a massive flood down the Feather and Sacramento Rivers.”

The developer plans to apply for 4% tax credits in May 2025 to help finance the $50.8 million project

According to court documents, the incident occurred on December 6, 2024, while Eric Aguirre was operating an Elk Grove city vehicle.

The six‑member California Commission on Judicial Performance publicly censured Judge Carrozzo on April 17, 2025.

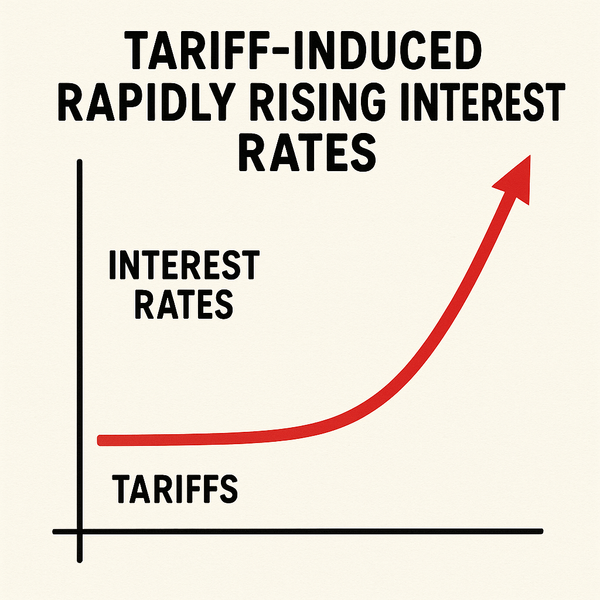

Mayor Singh-Allen must proceed cautiously with any large bond issuance, lest her legacy become that of the person who drove the city off a financial cliff.