Politicians punch holes in California’s sunshine laws

From CalMatters.org

From CalMatters.org

A sad day 30 years ago today.

The petitioners – the San Francisco Baykeeper, Restore the Delta, Delta counties and agencies, among others – vigorously opposed DWR’s motion.

While the former president's economic policy had its share of critics, Biden's policies offered businesses and the economy a degree of orthodoxy.

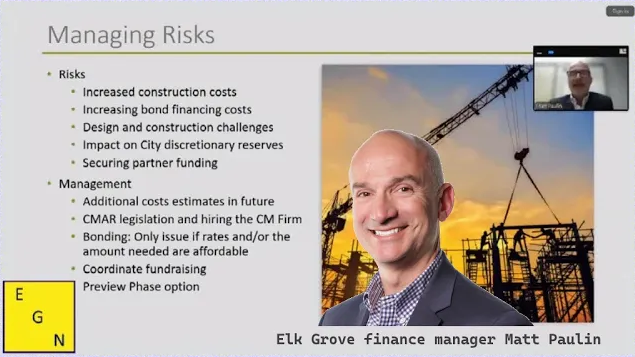

So, if interest rates have dropped, making construction feasible and cheaper, why hasn't the city rushed into issuing the bonds?